Many open source projects are rigorous on what they want to include in the project. It can be tough to convince the project lead of a new feature, even if you wrote a quality implementation and documentation of it. Sometimes it can be hard to even get a bugfix incorporated. It may feel that the maintainers are rude or arrogant, but most often there are good reasons not to take in the contributions. But it doesn’t mean your enhancement idea is worthless.

Many open source projects are rigorous on what they want to include in the project. It can be tough to convince the project lead of a new feature, even if you wrote a quality implementation and documentation of it. Sometimes it can be hard to even get a bugfix incorporated. It may feel that the maintainers are rude or arrogant, but most often there are good reasons not to take in the contributions. But it doesn’t mean your enhancement idea is worthless.

The most successful pieces of software are somewhat extensible. Operating systems would be nothing without a wide selection of applications. Your PC hardware would be rather boring, and probably more expensive, without an extensible OS kernel. Your Vaadin UI would probably be a really boring CRUD, without the hundreds of add-ons you can throw in via Directory. Quite often the core wouldn’t survive without a flourishing ecosystem of extensions.

Earlier I wrote about how to contribute code to OSS products. This week I’ll try to convince you that it is often better to write an add-on. Writing an extension is an easier and often better way to start contributing to larger projects.

Why extensions are better than core features

Built-in features are sure easier for new users to start with and may give the user a more coherent feeling. But that’s it. In pretty much all other aspects, add-ons, extensions, plugins, apps, and helper libraries are better than core features. Let me list a couple:

- The core is not bloated with features needed only by a fraction of the people.

- Maintenance work is easier to spread among a larger number of people.

- The release process is more agile - new features can be delivered faster.

- Experimental features can be tested with otherwise stable products.

- Backward incompatible changes are not a PITA for users, as they can stick to certain versions.

- Competing solutions for same use case can co-exist.

Often also the project maintainers, with all the rights to land their patches to the core, prefer to put certain features to an extension. Certain features are just better off as separate projects. Sometimes a feature, that should really end up in the core, is better to be developed as an extension in the beginning. Later, once it is stabilized, it can be incorporated as a core feature. Especially with software libraries like Vaadin, rewriting or dropping a feature altogether is much easier, when the feature isn’t shipped with the core distribution with backwards compatibility guarantees.

When writing extensions, you should really think of it as participation in an existing project, more than starting a new one. Extensions are such an essential part of many OSS software and their communities that they wouldn’t exist without them.

The types of extensions you can make varies. Some projects only allow pluggable completely new features, whereas others let you customize almost every feature of the product. For Vaadin, completely new UI components are the most common ones, but there are also a lot of extensions for the built-in features, such as extensions to the data Grid.

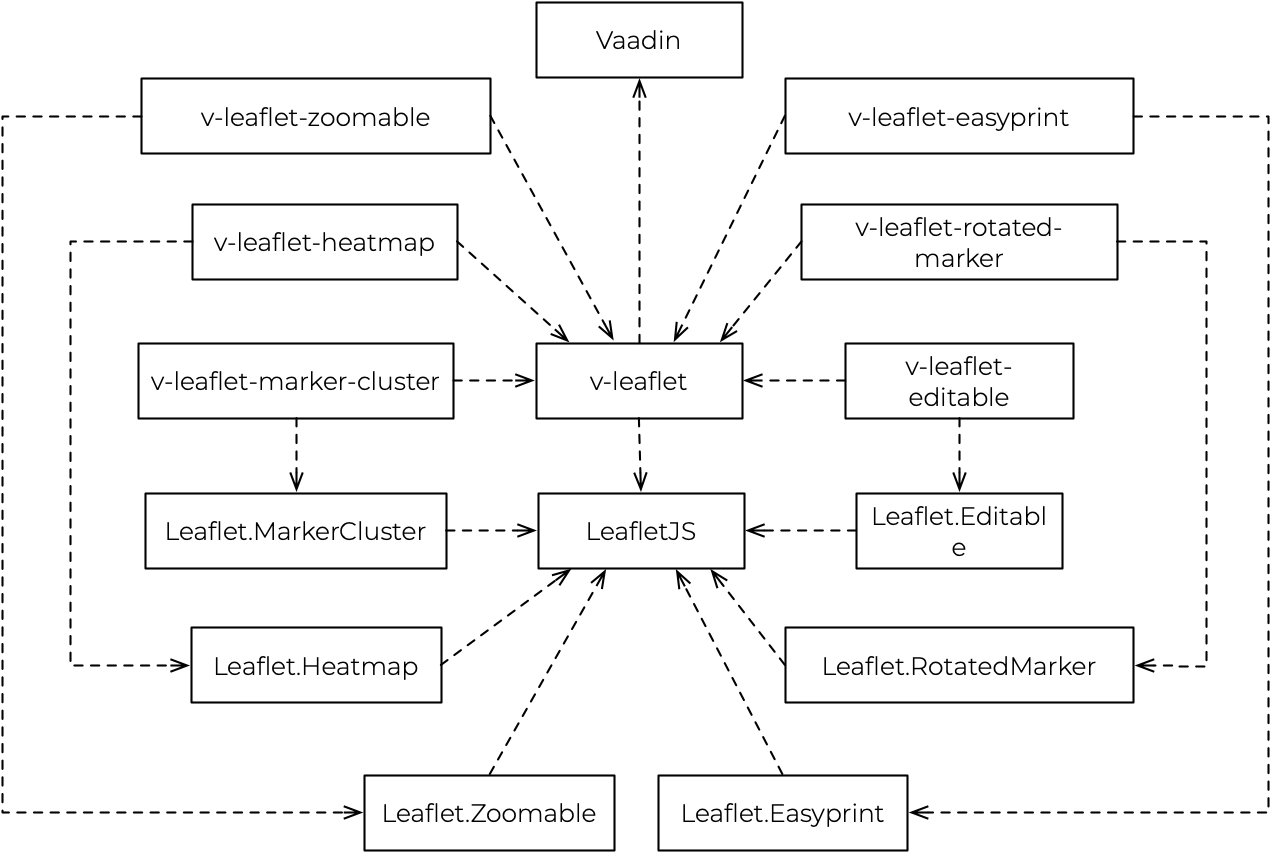

Extensions don’t have to stop on level one. In many cases, there are extensions to extensions and dependencies between them. Below you can see a diagram presenting LeafletJS, an open source slippy map library, some of its extensions, and how they connect to their Vaadin counterparts.

V-Leaflet is an extension to Vaadin and provides a Java API for LeafletJS. LeafletJS is a small slippy map component, which has numerous extensions, and V-Leaflet has extensions that provide Java API for those extensions. The diagram shows some of those extensions of extensions.

V-Leaflet is an extension to Vaadin and provides a Java API for LeafletJS. LeafletJS is a small slippy map component, which has numerous extensions, and V-Leaflet has extensions that provide Java API for those extensions. The diagram shows some of those extensions of extensions.

Share your extension in a platform-specific “app store”

Most software ecosystems have some central service for extensions. iPhone users are forced to only use Apple’s App Store to install apps to their smartphones. Android phones are not limited by operating system, but Google Play store is still easily the most common way how apps are installed. The success of the extension catalogs is not the fact that you have to use them, but that it is convenient to use them: easy to find if there is a solution for your problem and which of the solutions is the best fit for you.

If you write an extension to some OSS project, it is not actually a contribution, unless other users can find it. Many open source softwares have had some similar concept for their extensions even before iPhone. Some are tightly integrated to the apps, some have web front-ends. Here are a couple of examples:

- Eclipse Marketplace - IDE extensions

- NetBeans Plugin Portal - IDE extensions

- WordPress Plugins - Huge amount of extensions to the popular blogging platform

- Vaadin Directory - Extensions for the popular Java Web UI framework and Web Components

- LeafletJS plugins - Extensions for the free mobile friendly slippy map library.

- NPM - The package manager for JavaScript

- The Python Package Index - A list of Python packages

Give your baby a good life - use the extension catalogs and share your contributions with the rest of the community! Pushing your source code to GitHub is not enough. Many of the catalogs also contain instructions to get started with your extensions.