Why the solution to slow web apps isn’t a more complex set of tools

A while back I was working on an Angular app. What struck me was that Angular is not really only a framework, rather it’s an entire platform of its own built on top the Web platform. The reasoning behind this is to give developers a unified way of building apps across different platforms. But what’s the cost of using this abstraction?

For you, as a Web developer it means that for most things you know how to do on the Web, there’s a (slightly) different version of accomplishing that in Angular. It also means that you don’t have direct access to new web technologies as they come out, you need to wait for the Angular team to add support for them. ServiceWorker support is a good example.

Perhaps most importantly though, it means that there’s inevitably a layer of JavaScript running between your application code and the browser that is running the Angular platform. How does this impact performance?

Angular has put a lot of emphasis on performance in Angular 2 and subsequent releases. The performance builds a highly modular architecture, an Ahead-of-Time (AOT) compiler and pre-rendering. When writing the Angular app, though, I couldn’t help feeling like I could have built the same component-based application using Web Components and have it run directly in the browser. Surely, that would be faster?

Can we make things easier…and faster?

I got support for my idea at Chrome Dev Summit while listening to Alex Russell giving a strongly opinionated talk on Web app performance. He went as far as claiming that if you are using a framework, you are “failing by default” when it comes to performance. Frameworks are focusing on catering to developers, often at the cost of end users. The developer needs to consciously work (sometimes around the framework) to deliver a fast experience to their users. I caught up with Alex after his talk, and we had an interesting talk about how these problems get further worsened by real-life devices and networks.

At this point I was intrigued and wanted to see if I could, in fact, recreate the Angular with nothing but Polymer, and if that app would be faster than the optimized Angular application.

To keep things more focused, I split my findings into two posts. This first post will cover my initial question, can Web Components be used to build faster web experiences with less tooling? The second part will take a look at the actual developer experience of building an app with these two ways and how we could improve those.

Apps and oranges

Now some of you may be thinking that isn’t comparing Angular, a framework, with Polymer, a library, a bit like comparing apples and oranges. After all, one is meant for building applications while the other is only concerned with building components.

Well, as it turns out, the way you build apps out of component is by combining smaller components into more and more complex compositions until you end up with an app. So, to build a component-based app, all you need is a way to make components.

Both Angular and Polymer ship with their own set of tools to help developers. Most notably, both include a command line (CLI) tool that can be used to bootstrap new projects and build the app for deployment. Polymer also includes some framework-like features like support for routing.

My Test Setup

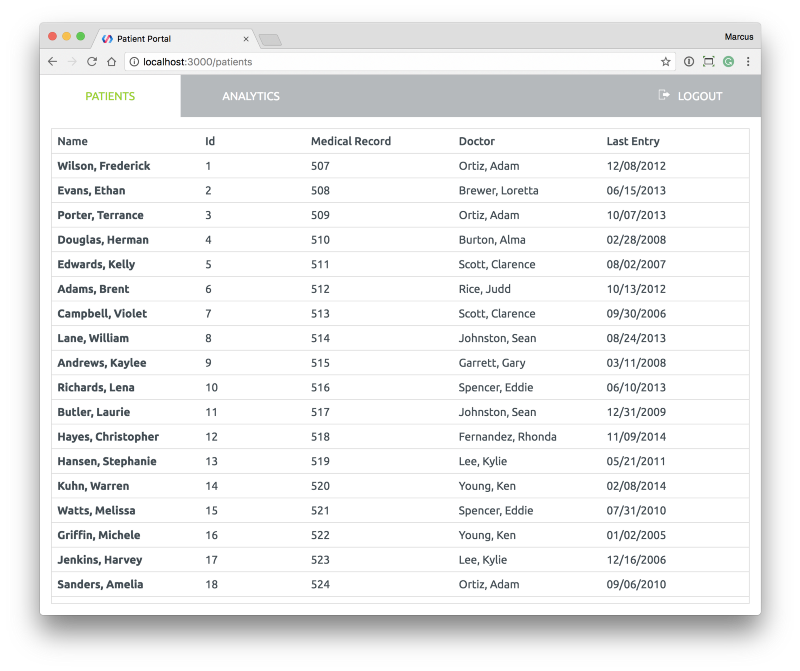

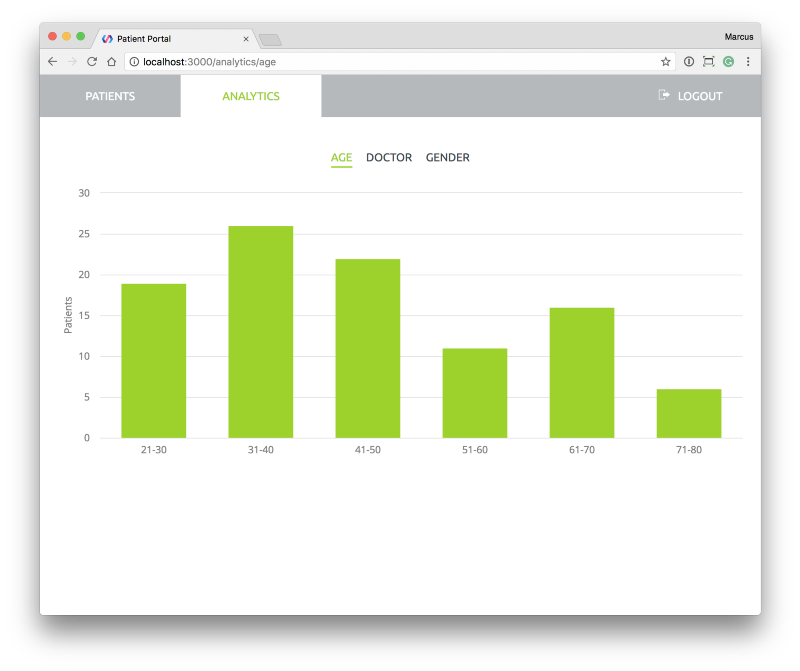

To compare the two approaches of building applications, I needed to build the same application with both. The application I developed is a mock portal application listing and showing stats for patients. It consists of three views: 1) a login view, 2) a listing view with master/detail editing, and 3) an analytics view showing chart data.

The Angular application uses Kendo Grid and Charts in addition to the core Angular framework. The Polymer app, in turn, uses Vaadin Grid and Charts. While the components are not identical, they are close enough in complexity and functionality to work for this comparison.

I built the applications following the instructions for production builds. For Angular 2, that meant using Ahead-of-Time (AOT) compilation and production mode in the build (ng build --aot --prod). For Polymer, I used polymer build to create a bundled build (concatenating dependencies into as few files as possible). Both apps used lazy loading of dependencies per view. The Polymer app build process additionally created a Service Worker that pre-loads subsequent views into cache while the user is logging in.

Both applications were served with Gzip enabled and communicated with the same REST API hosted on localhost. To get more realistic measurements, I used a simulated “Good 3G” connection with a “High-End Device” in Chrome Dev Tools.

I ran all tests with Chrome. I also ran a comparison test on webpagetest.org against versions deployed on GitHub pages.

How fast does this thing go?

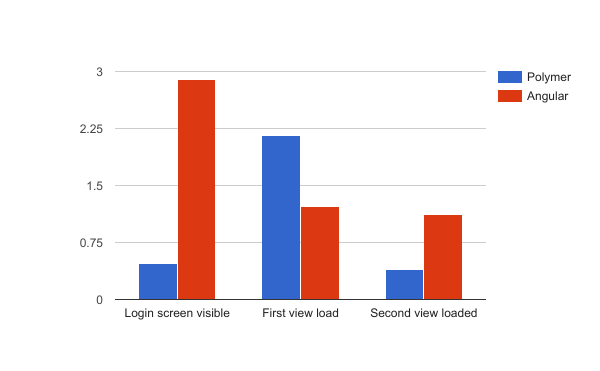

There was a very clear winner in terms of initial load speed. The Polymer-based app was visually complete and ready to be interacted with in just 0.8 seconds. It took the Angular app a whopping 4 seconds longer to get done (4.8s). For the initial load, Polymer was 6x faster than Angular.

Why is this? Even with AOT compilation, Angular 2 has two distinct disadvantages compared to Polymer. First, since everything is in JavaScript, it needs to get downloaded, parsed, and evaluated before anything can be shown to the user. Polymer, on the other hand, can use the browser’s built-in streaming capabilities to show the app as it’s being downloaded. Second, Web Components are browser-native constructs. No matter how optimized the JS is that Angular outputs, some things are just faster to run directly on the browser itself.

For the initial load, Polymer was 6x faster than Angular.

For subsequent page loads, the difference is much less drastic. There are some differences, but I suspect those boil down mostly to the components used on those pages (charts and data grid) than to the technology used. The chart below summarizes the performance measurements for the entire app.

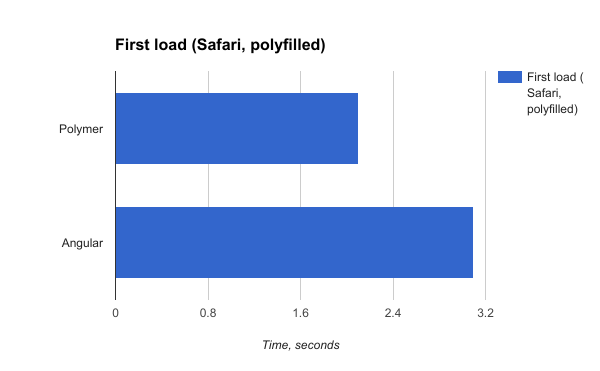

Interestingly, the app loads faster also when using Safari and the Web Components polyfill:

Both apps were roughly the same size in terms of download (Polymer: 630kB, Angular: 689kB) and lines of code (Polymer: 1999 lines, Angular: 1953 lines).

The full test can be found here.

So what about pre-rendering?

I could have used pre-rendering in the Angular app to improve the perceived speed. I say perceived because while pre-rendering lets the user see (a good estimation) of the finished page much faster, the added complexity can actually make it slower to get the page interactive. While the scripts are loading, the page looks complete, but nothing happens when a user tries to interact with the page.

There are other reasons, like SEO, why you might want to do pre-rendering, but as far as performance goes, I wanted to focus on how long it takes to get the app to a usable state.

It should be noted that Polymer does not support pre-rendering. Instead, the Polymer team is advocating for the use of the PRPL-pattern to achieve speeds comparable to pre-rendering without the added complexity of running the app both on the server and in the browser.

Conclusions

Web Components are fast. For the initial load, I was able to achieve a 6x speedup compared to the same app implemented in Angular. And I was able to achieve this speedup with a much simpler set of tooling — no AOT compilation, no pre-rendering.

But another question remains — can you build real, complex apps with only Web Components? It doesn’t do us much good that Web Components are fast if we’re not able to use them to build app. The strength of Frameworks is in the structure they offer to help developers build large, maintainable applications. This is something that Polymer or Web Components in general don’t offer.

In the second part of this article, I’ll dive into the developer experience of building these apps and what we might be able to do to make it easier for developers to build blazing fast web experiences.